The Octavien Brothers

© Martin Eidelberg

Created November 2022

© Martin Eidelberg

Created November 2022

François Octavien (1682-1740) is one of the lesser-known satellites of Antoine Watteau. Unlike Pater, Lancret, Quillard, and Mercier—Watteau followers whose works have been assiduously studied—the only two attempts to do this for Octavien were Jean Messelet’s slim chapter in Louis Dimier’s L’Art du dix-huitième siècle and an equally brief treatment by Robert Rey in his Quelques satellites de Watteau.1 Not only are Messelet’s and Rey’s studies a century old but they were minimal efforts, even in view of that era’s limited means. The time to reconsider the artist is well overdue.

A major step forward in charting this painter’s career was recently made by Guillaume Glorieux, who uncovered important data in French archives.2 As he discovered, the artist’s birth and death dates, as well as his whereabouts, had previously been confused with those of his younger brother, also named François Octavien (after 1682-1732), and other members of this family of painters. Adding to the confusion, these artists often signed their work simply as “Octavien.” Whereas our painter signed his works and legal documents with just his family name, his younger brother generally preferred “F. Octavien” and included a bar over the letter “n”. The older brother appears to have been the more talented of the two, but distinguishing their works is not fully resolved—a problem to which we will return later.

FRANÇOIS OCTAVIEN THE ELDER

|

1. François Octavien the Elder, La Foire de Bezons, c. 1725, oil on canvas, 135 x 195 cm. Paris, musée du Louvre. |

The one well-established fact in François Octavien the Elder’s career is that he was accepted into the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture on November 24, 1725, at which time he presented as his morçeau de réception the Foire de Bezons, now in the Louvre (fig. 1).3 That painting, an impressively large canvas, marks an important milestone in his career and also provides a touch stone by which we can measure other attributions to him. The composition features an expansive, flat terrain with deep extensions into the distance seen through alleés of trees. The artist has maintained the old tradition of emphasizing local color in the foreground and employing a blue-green palette for the distance. The carefully balanced figural staffage is equally distinctive—a group of well-dressed figures occupies the center left foreground and a surfeit of smaller figures are dispersed throughout the middleground and the distance. In overall effect, the composition resembles those found in seventeenth-century Netherlandish carnival scenes. The diminutive scale of the figures and the narrative delight in their activities prove to be characteristic of this artist’s work.

Although painted only a few years after Watteau’s death in 1721, Octavien’s picture shows surprisingly few specific links to Watteau’s oeuvre.4 While inconceivable without the master’s example, still, it is far from his idyllic scenes. Octavien’s picture seems more factual in its insistence in recording this outing with riders thundering in at the right, stray dogs wandering about, and its view of an actual town at the right.5 While the figures are Watteau-like, they do not depend on specific figures borrowed from the master’s pictures. Moreover, Octavien was not alone in pursuing the new genre of fêtes galantes. Watteau’s other satellites were also imitating and reshaping their master’s visual language in the third decade of the century. If Pater and Lancret loom largest, others such as Quillard, Octavien, and Bonaventure de Bar explored this genre as well. And there were other painters who remain anonymous. Remarkably, these men were all contemporaries of each other and worked in Watteau’s shadow, yet each found his own personal style.

A number of closely related fêtes galantes are rightly associated with François Octavien’s name. Among them are two pendants, both signed by the artist and dated 1727, that is, two years after he completed the Louvre picture (figs. 2, 3).6 Both are much smaller works, essentially a third the size of his morçeau de réception, but one is essentially a variation of that picture. The spatial arrangement is essentially the same, as is the trio of riders. The group of figures in the immediate foreground is similar, but not identical. The closeness of the two pictures reminds us that Octavien, like most painters of the time, tended to repeat himself or created variations on a theme.

|

4. François Octavien the Elder, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 122 x 177.8 cm. Bielefeld, Samuelis Baumgarte Galerie. |

Another related fête galante is a painting with the Samuelis Baumgarte Galerie (fig. 4). In a flight of fancy it was at times titled Le Parc de Petit Trianon à Versailles. In the early twentieth century the painting and an otherwise unidentified pendant traveled under a misattribution to Nicolas Lancret, a name far better known than Octavien’s. Some of the figures in the Baumgarte picture, especially the woman toward the left of the foreground group, do resemble Lancret’s, making one wonder if there was a relationship between the two artists. In the 1930s the two Baumgarte paintings were owned by George F. Baker of New York. Apparently his estate lent it (and perhaps the pendant?) to an art exhibition at the New York World’s Fair of 1939. One can only wonder what the pendant was.8 If the pendants sold in London are a guide, it might have been a variation of the Louvre picture.

|

5. François Octavien the Elder, Fête champetre, oil on canvas, 116 x 168 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Other equally ambitious, multi-figured fêtes galantes by Octavien have emerged. One is a picture that came to auction in Italy in 1987 (fig. 5).9 Comparable in size to the Louvre and Baumgarte canvases, it too has a similar triangular group of figures in the immediate foreground, centralizing the composition; other groups scattered across the middle ground; and a vast, flat terrain extending into the far distance. If nothing else, François Octavien the Elder was consistent or, one could say, formulaic in his approach.

|

6. François Octavien the Elder, Fête galante, oil on canvas, 77 x 109 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

We might consider yet another closely related fête by Octavien, one that appeared on the Paris market in 1973 (fig. 6).10 Its general composition differs slightly from those just considered: the grouping of figures in the immediate foreground appears to the left of center rather than on the central axis. However, as a whole the figures closely resemble those that we have already discussed, especially the man who stands over the recumbent figures. In addition, the division of the space into distinct zone, each differently colored, and the sense of deep space extending to the far distance are characteristics noted in the Octavien paintings previously discussed. Although this sixth picture is similar to those already introduced, the individual figures do not repeat those in the artist’s other paintings.

|

|

7. François Octavien the Elder, La Bascule, oil on canvas, 65 x 81.2 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

8. François Octavien the Elder, La Danse, oil on canvas, 65 x 81.2 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

In recent years a pair of somewhat smaller, more intimate fêtes galantes have appeared at auction (figs. 7, 8).11 Both works are signed but even without that aid we can recognize the by-now familiar characteristics of Octavien’s art, not only in the individual figures but also in their arrangement. In La Bascule, the seesaw and the children in the foreground are centralized, and the composition opens to distant views at the sides. So, too, the color differentiation between the foreground and background is pronounced. In the scene of dancing, the composition is not symmetrical but shifted to the right, while the flat terrain and color differentiation between foreground and background remain constants.

|

|

9. François Octavien the Elder, Pierrot desappointé, oil on canvas, 40 x 32 cm. Nancy, Musée des beaux-arts. |

10. François Octavien the Elder, La Répetition dans le parc, oil on canvas, 40 x 32 cm. Nancy, Musée des beaux-arts. |

Two paintings in the museum in Nancy present equally intimate groupings (figs. 9, 10). Vertical rather than horizontal compositions, and thus without expansive views into the distance, these sheltered gatherings among groves of trees resemble the groups in many of Watteau’s pictures, and even more so Lancret’s. Octavien’s authorship of these pendants is strengthened by their history. In the late eighteenth century they were in the collection of the comte and comtesse de Chamisso, who fled France during the Revolution, leaving their possessions behind.12 In 1793, they were transferred to the newly formed museum in Nancy and were listed as part of a group: “quatre tableaux dans le genre de Watteau representant des Espagnols dans des jardins.” Their attribution to Octavien is further supported by the artist’s signature on both works. The other two paintings from the Chamisso collection, also now in the Nancy museum, despite their having been listied under Octavien’s name in 1793, are clearly not by him and need not detain us.

|

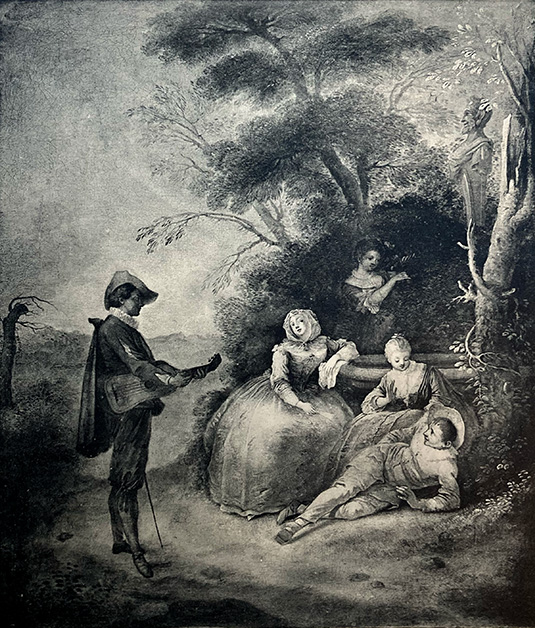

11. François Octavien the Elder, La Sérénade, oil on canvas, 79 x 63 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Another painting to be considered is one that was given to Octavien when it came up at auction in the mid-nineteenth century (fig. 11).13 One might wonder if this attribution were not still older, perhaps extending back to the eighteenth century. The attribution was still in place in the early twentieth century and the picture was cited by Messelet.14 But then it fell from sight and has not been seen for over a century.

|

|

12. Antoine Watteau, L’Enchanteur, oil on copper, 18.9 x 25.6 cm. Troyes, Musée des beaux-arts. |

13. Antoine Watteau, Pèlerinage à l’île de Cythère (detail), Berlin, Schloss Charlottenburg. |

While stylistically similar to the other Octavien fêtes galantes discussed above, this painting is exceptional in its dependence on specific inventions by Watteau. The overall composition of the standing guitarist serenading seated characters, and the pose of the guitarist—present in Octavien’s painting—depend on Watteau’s L’Enchanteur (fig. 12). Moreover, the figure of a woman gathering flowers corresponds to one in the Berlin version of Watteau’s Pèlerinage à l’île de Cythère (fig. 13) and also the Amusements champêtres, now in a New York private collection. To date, this is the only Octavien picture whose figures can be traced to specific sources in Watteau’s oeuvre.

|

14. François Octavien the Elder, The Charlatan, oil on canvas, 42 x 55 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

A last painting by François Octavien the Elder to be presented here is a scene of animated commedia dell’arte characters performing on a stage at a fair (fig. 14).15 The work is signed “Octavien” in the lower right corner, and the delineation of the characters, especially the faces of the people at the left, accords with his style. Not to be discounted is the manner in which the level terrain extends back to the distance, one of the artist’s penchants. This picture is particularly interesting because it reveals another aspect of his wide thematic range—a range typical of Watteau’s satellites.

Seen as a whole, these twelve paintings by François Octavien the Elder, and still others attributable to him reveal an artist of modest inspiration and power.16 While not of the first order, nonetheless the painter was skilled. However, there are a great many other paintings, often signed “Octavien,” that are different and are often markedly inferior. These have clouded our sense of his oeuvre.

FRANÇOIS OCTAVIEN THE YOUNGER

One of the momentous discoveries made by Guillaume Glorieux is that François Octavien the Elder had a younger brother, also named François, who likewise was an artist. For the sake of clarity, I shall call him “François the Younger,” although that is usually an appellation reserved for sons. Like his older brother, he is little known. He too was apparently born in Rome and came to France with his family. Working in Paris, he was prolific. Although many of his pictures are closely related to those of his brother, he was the decidedly less talented of the two. His figures are less gracious and charming, and his compositions are dry and somewhat arid.

|

15. François Octavien the Younger, Troops Outside an Inn, oil on panel, 37 x 45.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

|

16. François Octavien the Younger, A Military Encampment, oil on panel, 37 x 45.5 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

The younger Octavien was drawn to scenes of military camps and troops on the march. Following in the shadow of Watteau and also maintaining a longstanding Netherlandish genre of depicting everyday army life. Two small paintings of soldiers by François the Younger, both signed and both on panel (a support we have not encountered until now) suggest what we might expect from the artist (figs. 15, 16).17 His figure types, such as the woman in the left foreground struggling with a soldier outside an inn, and his sense of distant space in the pendant, have parallels with the work of his older brother.

|

17. Nicolas Lancret, A Military Camp, oil on panel, 17.5 x 22 cm. New York, collection of Mary Tavener Holmes. |

Octavien’s distribution of figures across the canvas in his Military Encampment and their general deportment, while related to Watteau compositions such as his Détachement faisant alte, also parallel contemporary military compositions by Watteau’s other satellites, such as those by Lancret (fig. 17).

Two small fêtes galantes previously thought to be by his older brother, can be added to the oeuvre of François the Younger (figs. 18, 19).18 Although not unrelated to compositions by his sibling, they suffer in comparison. The simplistic positioning of the figures at the center, the minimal modeling of facial features, and the dead tree trunk at the right are elements already in his brother’s pictures, but the overall aridity of the works is unfortunate.

Four pendant pictures by François the Younger appeared at auction in Nice in 1974 (figs. 20-23).19 Here too there is a marked lack of modeling of facial features and a paucity of spirit. Two of them, fêtes in the countryside (figs. 20, 21), are cut from the same cloth as the preceding two works: diminutive figures, minimal modeling, symmetrical compositions, dead tree trunks.

Also included in the lot sold in Nice were an additional two paintings by the artist (figs. 22, 23). But whereas the previous two were clearly pendants, matching each other in composition and subject, the remaining two are somewhat dissimilar. One depicts an indoor setting and features two dancers in commedia dell’arte costumes. The fourth work in this ensemble is equally dissimilar: although it portrays a fête galante in a landscape, the couple is proportionately larger and thus not in scale with the other three pictures. Moreover, although it was painted by François Octavien the Younger, the composition is not his. It is a direct copy of Watteau’s La Contredanse, now in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. This reveals an unsuspected aspect of his career—his work as a copyist—but it accords with the undistinguished quality of his oeuvre. He certainly was no Watteau, nor even equal to his older brother.

|

|

24. François Octavien the Younger, Spring, oil on canvas, 74 x 60 cm. Angers, Musée des beaux-arts. |

25. François Octavien the Younger, Winter, oil on canvas, 74 x 60 cm. Angers, Musée des beaux-arts. |

Of better quality are two allegories of the seasons in the Musée des beaux-arts of Angers (figs. 24, 25). Originally in the collection of Pierre Louis Éveillard de Livois, a local amateur of the fête galante, they were confiscated and sent in 1799 to the city’s nascent museum with other booty from the French Revolution. While in the museum they were given to Nicolas Lancret, an attribution that remained in place until recently. Late in the twentieth century they were reattributed to Jacques de Lajoüe (1886-1761), an artist best remembered for his depictions of fanciful rococo structures, most often enlivened by figures borrowed from Jean de Jullienne’s engravings after Watteau.20 Lancret’s name was intoned as a possible second collaborator in these paintings. Most recently, the pictures have been given to Lajoüe alone. However, neither Lancret nor Lajoüe had a hand in them. The rather ordinary architecture seen here has nothing in common with Lajoüe’s imaginative follies, and the figures betray the hand of François Octavien the Younger. Moreover, the scene of Winter is repeated with only minor changes in a painting that he signed (fig. 28).

It must be emphasized that the Angers compositions are not new inventions. They are, as Guillaume Faroult rightly recognized, close copies after paintings by Jean-Baptiste Pater (figs. 26, 27). The Angers Spring follows Pater’s design with only minor modifications. As can be seen, there is an additional man in the left foreground of Spring, an urn atop a pedestal has been added, and large, picturesquely bent trees have been inserted at the right. Similarly, there are additional trees in the Angers Winter. We have already observed that François the Younger executed a copy of Watteau’s La Contredanse (fig. 23), and this opens the question, then, of how many of the otherwise anonymous copies after Watteau and his many satellites may prove to be the work of François Octavien the Younger.

|

28. François Octavien the Younger, Winter Landscape, oil on canvas, 72 x 90 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

François the Younger’s Winter Landscape (fig. 28) is a slightly expanded, horizontal version of his picture in Angers (figs. 25). It too is signed. The primary figures still echo Pater’s composition but additional characters—the couple at the left, the two youths in the foreground, some of the small figures in the background, and the jumping dogs—help create a lively mood. When the painting, which is signed “Octavien,” was recently on the Paris art market it was naturally assumed to be by the senior François Octavien but, as its style demonstrates, it is by his younger brother.21 This frosty scene was one to which the artist returned on several occasions, producing simpler variations.22

|

29. François Octavien the Younger, La Sieste, oil on canvas, 34.3 x 28 cm. Whereabouts unknown. |

Another small fête galante that can be given to François the Younger is known as La Sieste (fig. 29). In the late 1920s when the picture first came to public attention, it was owned by Elizabeth Wildenstein, the sister of Georges Wildenstein and the wife of the dealer Louis Paraf. It was attributed to Philippe Mercier when it figured in the 1929 Paris exhibition, Le XVIIIe siècle aux champs, and in the 1935 exhibition of French eighteenth-century art in Copenhagen.23 Although never officially refuted, the attribution to Mercier was not cited, for example, in John Ingamells and Robert Raines’ catalogue raisonné of Mercier’s works.24 Then, when it reappeared in a New York auction in 2011, it bore the equally improbable ascription, "attributed to Pierre Antoine Quillard."25 The picture was clearly not by Mercier or Quillard but, not having a proper attribution when I considered the work in 2011, I dubbed the artist “the Sieste Master.”26 Now it is apparent that the responsible artist was François Octavien the Younger. The simplicity of the composition, the rudimentary facial features, the dryness of the flat terrain—all these are hallmarks of his art.

The many paintings by François the Younger that have been presented here are astounding in their variety and number—especially because his existence was unsuspected until just a few years ago. Moreover, there are still other pictures, many of them promising candidates, that need to be considered but issues of time and space make it necessary to postpone consideration of them until a future occasion.

DRAWINGS BY THE OCTAVIEN BROTHERS

While we now have a better sense of the two brothers and their work, there has been no mention of their activity as draftsmen. Only rarely have drawings been identified with “Octavien,” meaning the elder Octavien since he was the only one known. Unfortunately, as will be shown, these attributions prove largely spurious.

We might expect to find references to Octavien drawings in eighteenth-century auction catalogues, but there seem to be none. Nor have any been identified in nineteenth-century catalogues. Collectors, such as Paignon de Dijonval, despite his wide, catholic taste, did not own any. Most scholars of the older brother’s oeuvre have ignored this issue. In his admittedly brief survey of Octavien’s oeuvre, Messelet did not catalogue any drawings.27 Nor were any cited in the standard bibliographies of the artists, such as those in Thieme and Becker, and also Bénézit.28 So too Glorieux skirted the issue. Likewise, in his overview of drawings by Watteau’s satellites, Moulinier omitted all mention of the Octaviens.29 However, much to his credit, Robert Rey cited a number of drawings that had been attributed to the artist in the past, but, of course, even Rey’s account is now a century old and his selection is not cogent.30

Rey cited two red chalk drawings that were attributed to Octavien, presumably François the Elder, when they were in the Lions collection in the nineteenth century, and that then passed to the Del Campo collection.31 One showed a woman playing a vielle, and included foliage at both sides. The other showed a shepherdess with a crook, again with foliage and a distant building in the background. Unfortunately, the basis for the attribution of the two sheets to Octavien was never explained, nor were they illustrated. Neither drawing can be traced into the twentieth century, and without more documentation, these attributions remain nebulous.

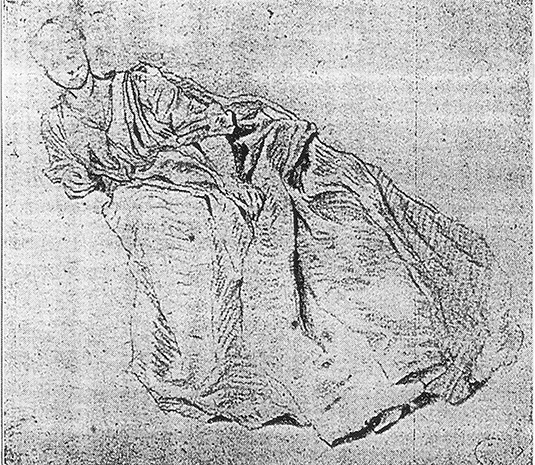

Another drawing that was attributed to the older Octavien brother, one that came up at auction several decades ago, is a study of a reclining woman seen from behind (fig. 30).32 While the drawing does seem to be a French eighteenth-century work, the rationale for assigning it to Octavien is not apparent. The drawing is not signed, nor does it correspond to a specific figure in any of his paintings. Rather, the physiognomy of the face, especially the accented cheek, and the fluid draftsmanship suggest the work of Pater and his followers. Also, her pose seen from behind, leaning—almost recoiling—to one side, is a characteristic motif often seen in Pater’s paintings and drawings (fig. 31).

A red chalk drawing of a seated woman playing a musical instrument and attributed to Octavien appeared on the Paris auction market in 2010.33 We know little about it. It was not illustrated at the time, and even the musical instrument was left unnamed. It apparently was not signed, and it was not related to any established Octavien painting. Also not in its favor, the drawing did not sell.

Another drawing that has been wrongly ascribed to Octavien is a red and black chalk study of a standing man that appeared at a Paris auction in 1983 (fig. 32).34 Previously, when it was in the John Postle Hesseltine collection, it had been given to Watteau. One can appreciate why Watteau’s name had been proposed, but it is less apparent why Octavien’s name was substituted, especially since the man is unrelated to any figure in an Octavien painting, and there is no known Octavien drawing to which it could have been compared. Whatever the reason was, the drawing is not by Octavien. In fact, it is by Philippe Mercier and was used by him for a figure at the right side of one of his paintings, A Bowling Party (fig. 33).35

|

|

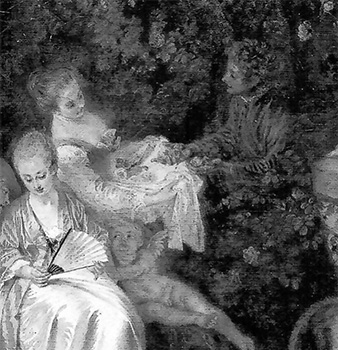

34. François Octavien the Younger, Study of a Recumbent Woman, red chalk, 14.9 x 16.5 cm. Grenoble, Musée des beaux-arts. |

35. François Octavien the Younger, La Sieste (detail). |

A more rewarding path is offered by a red chalk drawing in the Musée des beaux of Grenoble (fig. 34). By 1909, when it was published in the museum’s catalogue, it was given, expectably, to Watteau.36 As it is far from his masterful draftsmanship, this idea was never repeated in the Watteau literature. In their recent catalogue of Watteau’s drawings, Rosenberg and Prat rightly dismissed the claim; all they opined was that the drawing was French c. 1720.37 However, as I pointed out in my previous study of the Sieste Master, this study corresponds exactly to the woman in white in his eponymous work (figs. 29, 35). Her posture, the specific folds of the drapery, even the minimally delineated facial features, establish beyond doubt that this drawing was used for the painting. Now that we know that the painting is by François the Younger, we can safely conclude that the drawing is his as well.

In regard to drawings attributable to the older Octavien, I would propose an otherwise anonymous study of a seated woman whose whereabouts are unknown (fig. 36). When the sheet came up at auction in 1959 it was attributed to Nicolas Lancret.38 However, it does not show Lancret’s sharp, angular features. Many of the drawing’s prime aspects—especially the opposed directions of her torso and head, and the small, minimally indicated facial features—recall figures in Octavien’s paintings, such as the woman at the center of the fête galante formerly in the Cuttierrez du Estrada collection (fig. 37).

These two drawing extend the hope that additional drawings attributable to the Octavien brothers will be identified in the future. Their oeuvre of paintings is substantial and surely they made drawings for the figures in them. The hope is that eventually some will be found. Undoubtedly they are presently misclassified under the name of Watteau or his other satellites.

NOTES

1 Jean Messelet, “Octavien,” in Louis Dimier, ed., L’Art du dix-huitième siècle, 2 vols. (Paris: 1928), 2: 335-40; Robert Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau (Paris and Brussels: 1928), 101-31.

2 Guillaume Glorieux, “Un Peintre peut en cacher un autre: François Octavien (1682-1740) et son frère,” Techné, nos. 30-31 (2009-10), 218-27.

3 For more on the Louvre painting, see Patrick Ramade and Martin Eidelberg, ed., Watteau et la fête galante, exh. cat. (Valenciennes: Musée des beaux-arts, 2004), 132, 277.

4 Some critics have noted that the cavalier in the center background helping his lady dismount is similar to one in Watteau’s Partie de chasse in the Wallace Collection, and that this motif ultimately derives from a similar couple in Callot’s Foire d’impruneta. But, after all, such activity is natural to scenes of people arriving at an outdoor celebration.

5 In Marie-Catherine Sahut’s report on the painting, a copy of which is in the file of the Service de documentation, musée du Louvre, the curator questioned whether the horses and riders were not executed by a second artist. However, that would go against the Academy’s rules and, moreover, a similar horse and rider are among the subjects that the artist employed for a suite of etchings that he executed.

6 London, Sotheby’s, July 6, 2000, lot 224. The provenance of these paintings, while not continuous is well documented. In the early twentieth century they were in the Florentine collection of Dr. Ludwig von Bürkel and were sold in Munich, Helbing, October 29, 1910, lots 45-46. At mid-century they were with the New York firm of A. & R. Ball, and were temporarily consigned to French and Co. of New York in 1953-55. They were sold in London, Sotheby’s, December 10, 1980, lot 45, and were subsequently in Würzburg with Albrecht Neuhaus.

7 Baker’s ownership of the painting and its exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair are attested to in a letter dated May 18, 1988, from Oskar Scheidwimmer to Korad Ellerhorst. At the World's Fair, it was lot 207 and was ascribed to Lancret. See the advertisement when it re-appeared for sale in New York, William Doyle Galleries, Connoisseur (September 1980), 37. After World War II the gallery owner Oskar Scheidwimmer of Munich bought it from the Baker estate, and sold it to a private collection in Hamburg. In 1988 Scheidwimmer sold the picture to Korad Ellerhorst of Bremen, and it recently passed to the Baumgarte gallery.

8 The pendant was cited in a May 18, 1988, letter from Scheidwimmer to Ellerhorst.

9 Venice, Finarte, November 28, 1987, lot 342.

10 Paris, Hôtel Drouot (Ader Picard Tajan), May 14, 1973, lot 144, ”attribué à François Octavien.” Previously the painting appeared in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, November 24, 1972, lot 199.

11 London, Bonham’s, July 7, 2020, lot 38. Their previous provenance is listed as Paris, collection of the duc de Morny; Lady Emily Fitzmaurice,; A. H. E. Digby; F. I. Leggatt (c. 1920); Paris, Sotheby’s, June 24, 2009, lot 53; London, Bonham’s, October 23, 2019, lot 438.

12 For the early history of these paintings, see Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, 123-27.

13 Paris, sale, Quénisson collection, January 18, 1869, lot 66.

14 Messelet, “Octavien,” 129.

15 The Charlatan appeared at auction a decade ago: Paris, Hôtel Drouot (Ferri), April 13, 2012, lot 3. Also, Paris, Hôtel Drouot (Ferri), June 29, 2012, lot 2. Despite the presence of a signature, the painting was cautiously classified as “attribué à Francois Octavien.”

16 Consider, for example, two versions of a hunting party attributed to François Octavien the Elder. One in an oval format appeared in Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot Richelieu, Jean Barville collection, June 9, 2006, lot 6. A rectangular version appeared in Paris, sale, Tajan, October 27, 2017, lot 96.

17 For these works, see Paris, Galerie Cailleux, Watteau et sa géneration (1968), cat. 14-15. Both have since appeared at auction: Paris, Tajan, December 20, 1989, lot 120; Monaco, Christie’s, December 7, 1991, lot 55.

18 Sale, Paris, Palais Galliera, March 27, 1971, lot 26.

19 Nice, Galerie Robiony, February 20-21, 1974, lots 62, 63.

20 Marianne Roland Michel, Lajoüe et l’art rocaille (Paris: 1984), 78, 80-81, cat. P. 136-37. See also Guillaume Faroult in Angers, Musée des beaux-arts d’Angers, Chefs-d’oeuvre du musée des beaux-arts d’Angers (ParIs: 2004), cat. 58, 59.

21 Paris, Millon & Associés, June 20, 2022, lot 19. The annotations on the reverse side of a photograph of the picture indicate that it was on the Paris art market c. 1966.

22 See, for example, the variant of Winter presented in Paris, Christie’s, June 22, 2006, lot 35; Paris, Christie’s, April 16, 2007, lot 490. In both instances, misled by the attribution of the Angers paintings to Lajoüe, the Christie’s painting was similarly classified as “attribué à Jacques de Lajoue.”

23 Le XVIIIe siècle aux champs, exh. cat. (Paris: Bagatelle, 1929), cat. 48; Exposition de l’art français au XVIIIe siècle, exh. cat. (Copenhagen: Charlottenburg Palace, 1935), cat. 136.

24 John Ingamells and Robert Raines, “A Catalogue of the Paintings, Drawings and Etchings of Philip Mercier,” Walpole Society Journal 46 (1976-78), 1-70.

25 New York, Christie's, January 26, 2011, lot 175.

26 Martin Eidelberg, “The Sieste Master,” http://watteauandhiscircle.org/sieste.htm.

27 Messelet, “Octavien,” 335-40.

28 “Octavien” in Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, ed. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, 37 vols. (Leipzig: 1907-1950), 25: 558; “Octavien” in Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs et graveurs, 3 vols. (Paris:1924), 3: 381.

29 Axel Moulinier, Les Satellites de Watteau (Paris: 2020).

30 Rey, Quelques satellites de Watteau, passim.

31 As of the present it has not been possible to trace these collections.

32 Paris, sale, Hôtel Drouot (Loudmer), December 15, 1992, lot 3.

33 Paris, Hôtel Drouot (Millon & Associés), June 25, 2010, lot 125, 16.5 x 11 cm.

34 Paris, Hôtel Drouot, June 16, 1983, lot 10.

35 For the attribution to Mercier, see Eidelberg, “Philippe Mercier as a Draftsman,” Master Drawings, 44 (Winter 2006), 416.

36 Léon de Beylié, Le Musée de Grenoble: peintures, dessins, marbres, bronzes, etc. (Paris: 1909), XXVII, 147. Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, 1684-1721, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996), 3: cat. R 392.

37 Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Antoine Watteau, 1684-1721, catalogue raisonné des dessins, 3 vols. (Milan: 1996), 3: cat. R 392.

38 Paris, Galerie Charpentier, June 8-9, 1959, lot 138.